Polish Philosophy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of philosophy in Poland parallels the evolution of

The formal history of

The formal history of  From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature

From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature

The spirit of Humanism, which had reached Poland by the middle of the fifteenth century, was not very "philosophical." Rather, it lent its stimulus to linguistic studies, political thought, and scientific research. But these manifested a philosophical attitude different from that of the previous period.

The spirit of Humanism, which had reached Poland by the middle of the fifteenth century, was not very "philosophical." Rather, it lent its stimulus to linguistic studies, political thought, and scientific research. But these manifested a philosophical attitude different from that of the previous period.

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian.

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian.  A star among the pleiade of progressive political philosophers during the Polish Renaissance was

A star among the pleiade of progressive political philosophers during the Polish Renaissance was  Another notable political thinker was Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki (1530–1607), best known in Poland and abroad for his book ''De optimo senatore'' (The Accomplished Senator, 1568). It propounded the view—which for long got the book banned in England, as subversive of monarchy—that a ruler may legitimately govern only with the sufferance of the people.

After the first decades of the 17th century, the wars, invasions and internal

Another notable political thinker was Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki (1530–1607), best known in Poland and abroad for his book ''De optimo senatore'' (The Accomplished Senator, 1568). It propounded the view—which for long got the book banned in England, as subversive of monarchy—that a ruler may legitimately govern only with the sufferance of the people.

After the first decades of the 17th century, the wars, invasions and internal  The Polish dissenters created an original ethical theory radically condemning evil and violence. Centers of intellectual life such as that at Leszno hosted notable thinkers such as the Czech pedagogue,

The Polish dissenters created an original ethical theory radically condemning evil and violence. Centers of intellectual life such as that at Leszno hosted notable thinkers such as the Czech pedagogue,

After a decline of a century and a half, in the mid-18th century, Polish philosophy began to revive. The hub of this movement was Warsaw. While Poland's capital then had no institution of higher learning, neither were those of Kraków, Zamość or Wilno any longer agencies of progress. The initial impetus for the revival came from religious thinkers: from members of the Piarist and other teaching orders. A leading patron of the new ideas was Bishop

After a decline of a century and a half, in the mid-18th century, Polish philosophy began to revive. The hub of this movement was Warsaw. While Poland's capital then had no institution of higher learning, neither were those of Kraków, Zamość or Wilno any longer agencies of progress. The initial impetus for the revival came from religious thinkers: from members of the Piarist and other teaching orders. A leading patron of the new ideas was Bishop

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of

At the turn of the nineteenth century, as Immanuel Kant's fame was spreading over the rest of Europe, in Poland the Enlightenment philosophy was still in full flower. Kantism found here a hostile soil. Even before Kant had been understood, he was condemned by the most respected writers of the time: by Jan Śniadecki, Staszic,

At the turn of the nineteenth century, as Immanuel Kant's fame was spreading over the rest of Europe, in Poland the Enlightenment philosophy was still in full flower. Kantism found here a hostile soil. Even before Kant had been understood, he was condemned by the most respected writers of the time: by Jan Śniadecki, Staszic,  Another Polish proponent of Kantism was

Another Polish proponent of Kantism was  The Kantian and Scottish ideas were united in typical fashion by Jędrzej Śniadecki (1768–1838). The younger brother of Jan Śniadecki, Jędrzej was an illustrious scientist, biologist and physician, and the more creative mind of the two. He had been educated at the universities of Kraków, Padua and Edinburgh and was from 1796 a professor at Wilno, where he held a chair of

The Kantian and Scottish ideas were united in typical fashion by Jędrzej Śniadecki (1768–1838). The younger brother of Jan Śniadecki, Jędrzej was an illustrious scientist, biologist and physician, and the more creative mind of the two. He had been educated at the universities of Kraków, Padua and Edinburgh and was from 1796 a professor at Wilno, where he held a chair of

In the early nineteenth century, following a generation imbued with

In the early nineteenth century, following a generation imbued with

The Positivist philosophy that took form in Poland after the

The Positivist philosophy that took form in Poland after the

This movement, which had begun still earlier in Austrian-ruled

This movement, which had begun still earlier in Austrian-ruled  The movement's leader was Prus' friend, Julian Ochorowicz (1850–1917), a trained philosopher with a doctorate from the University of Leipzig. In 1872 he wrote: "We shall call a Positivist, anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."

The Warsaw Positivists—who included faithful Catholics such as Father Franciszek Krupiński (1836–98)—formed a common front against Messianism together with the Neo-Kantians. The Polish Kantians were rather loosely associated with Kant and belonged to the Positivist movement. They included Władysław Mieczysław Kozłowski (1858–1935), Piotr Chmielowski (1848–1904) and Marian Massonius (1862–1945).

The movement's leader was Prus' friend, Julian Ochorowicz (1850–1917), a trained philosopher with a doctorate from the University of Leipzig. In 1872 he wrote: "We shall call a Positivist, anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."

The Warsaw Positivists—who included faithful Catholics such as Father Franciszek Krupiński (1836–98)—formed a common front against Messianism together with the Neo-Kantians. The Polish Kantians were rather loosely associated with Kant and belonged to the Positivist movement. They included Władysław Mieczysław Kozłowski (1858–1935), Piotr Chmielowski (1848–1904) and Marian Massonius (1862–1945).

The most brilliant philosophical mind in this period was

The most brilliant philosophical mind in this period was

Even before Poland regained independence at the end of World War I, her intellectual life continued to develop. This was the case particularly in Russian-ruled Warsaw, where in lieu of underground lectures and secret scholarly organizations a '' Wolna Wszechnica Polska'' (Free Polish University) was created in 1905 and the tireless Władysław Weryho (1868–1916) had in 1898 founded Poland's first philosophical journal, ''Przegląd Filozoficzny'' (The Philosophical Review), and in 1904 a Philosophical Society.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 3, p. 356.

In 1907 Weryho founded a Psychological Society, and subsequently Psychological and Philosophical Institutes. About 1910 the small number of professionally trained philosophers increased sharply, as individuals returned who had been inspired by Mahrburg's underground lectures to study philosophy in Austrian-ruled

Even before Poland regained independence at the end of World War I, her intellectual life continued to develop. This was the case particularly in Russian-ruled Warsaw, where in lieu of underground lectures and secret scholarly organizations a '' Wolna Wszechnica Polska'' (Free Polish University) was created in 1905 and the tireless Władysław Weryho (1868–1916) had in 1898 founded Poland's first philosophical journal, ''Przegląd Filozoficzny'' (The Philosophical Review), and in 1904 a Philosophical Society.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 3, p. 356.

In 1907 Weryho founded a Psychological Society, and subsequently Psychological and Philosophical Institutes. About 1910 the small number of professionally trained philosophers increased sharply, as individuals returned who had been inspired by Mahrburg's underground lectures to study philosophy in Austrian-ruled

Kraków as well, especially after 1910, saw a quickening of the philosophical movement, particularly at the Polish Academy of Learning, where at the prompting of

Kraków as well, especially after 1910, saw a quickening of the philosophical movement, particularly at the Polish Academy of Learning, where at the prompting of

Those who distinguished themselves in Polish philosophy in these pre- World War I years of the twentieth century, formed two groups.

One group developed apart from

Those who distinguished themselves in Polish philosophy in these pre- World War I years of the twentieth century, formed two groups.

One group developed apart from  The second group of philosophers who started off Polish philosophy in the twentieth century had an academic character. They included

The second group of philosophers who started off Polish philosophy in the twentieth century had an academic character. They included

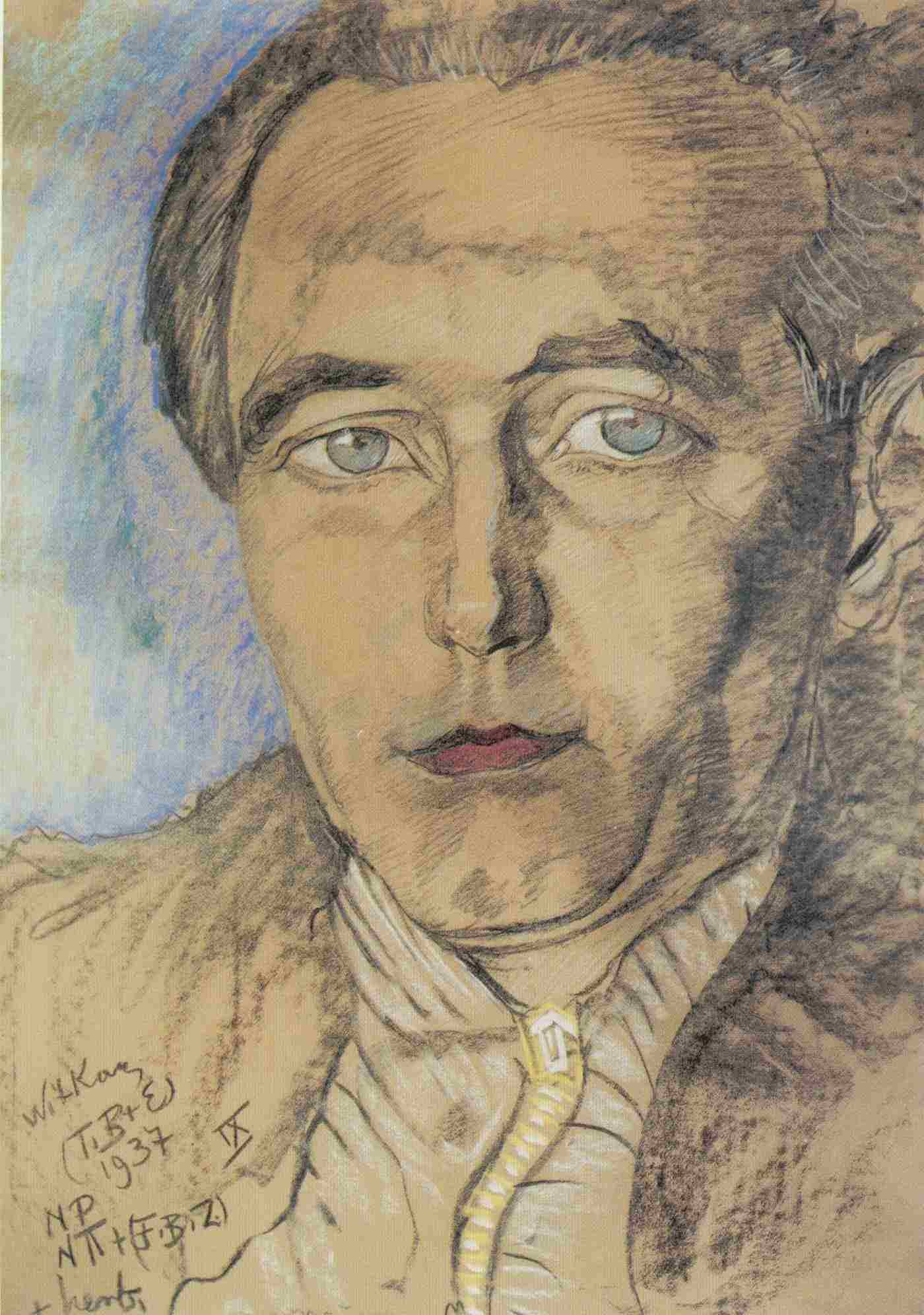

A characteristic of the interbellum was that maximalist, metaphysical currents began to fade away. The dominant ambition in philosophical theory now was not breadth but precision. This was a period of

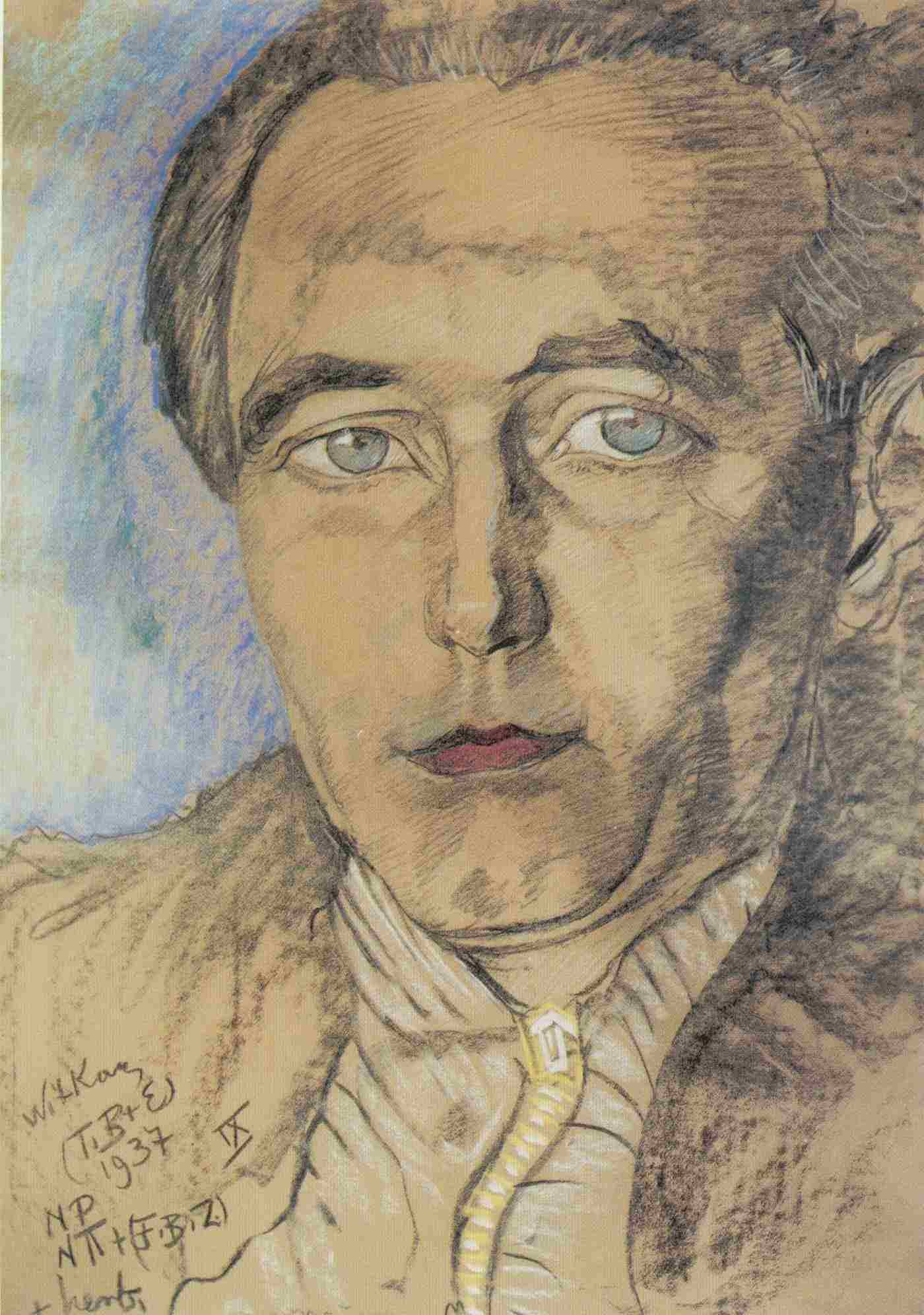

A characteristic of the interbellum was that maximalist, metaphysical currents began to fade away. The dominant ambition in philosophical theory now was not breadth but precision. This was a period of  A few individuals did develop a general philosophical outlook: notably, Tadeusz Kotarbiński (1886–1981), Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885–1939), and Roman Ingarden (1893–1970).

Otherwise, however,

A few individuals did develop a general philosophical outlook: notably, Tadeusz Kotarbiński (1886–1981), Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1885–1939), and Roman Ingarden (1893–1970).

Otherwise, however,  After Petrażycki's death, the outstanding legal philosopher was

After Petrażycki's death, the outstanding legal philosopher was  For some four decades following World War II, in Poland, a disproportionately prominent official role was given to

For some four decades following World War II, in Poland, a disproportionately prominent official role was given to

10 Polish Philosophers that Changed the Way We Think

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20160312013857/http://segr-did2.fmag.unict.it/~polphil/PolHome.html Polish Philosophy Page {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Philosophy In Poland Poland

philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

in Europe in general.

Overview

Polish philosophy drew upon the broader currents of European philosophy, and in turn contributed to their growth. Some of the most momentous Polish contributions came, in the thirteenth century, from theScholastic

Scholastic may refer to:

* a philosopher or theologian in the tradition of scholasticism

* ''Scholastic'' (Notre Dame publication)

* Scholastic Corporation, an American publishing company of educational materials

* Scholastic Building, in New Y ...

philosopher and scientist Vitello, and, in the sixteenth century, from the Renaissance polymath Nicolaus Copernicus.

Subsequently, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth partook in the intellectual ferment of the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, which for the multi-ethnic Commonwealth ended not long after the 1772-1795 partitions and political annihilation that would last for the next 123 years, until the collapse of the three partitioning empires in World War I.

The period of Messianism, between the November 1830 and January 1863 Uprisings, reflected European Romantic

Romantic may refer to:

Genres and eras

* The Romantic era, an artistic, literary, musical and intellectual movement of the 18th and 19th centuries

** Romantic music, of that era

** Romantic poetry, of that era

** Romanticism in science, of that e ...

and Idealist trends, as well as a Polish yearning for political resurrection. It was a period of maximalist metaphysical systems.

The collapse of the January 1863 Uprising prompted an agonizing reappraisal of Poland's situation. Poles gave up their earlier practice of "measuring their resources by their aspirations" and buckled down to hard work and study. " Positivist", wrote the novelist Bolesław Prus' friend, Julian Ochorowicz, was "anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."

The twentieth century brought a new quickening to Polish philosophy. There was growing interest in western philosophical currents. Rigorously-trained Polish philosophers made substantial contributions to specialized fields—to psychology, the history of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

, the theory of knowledge, and especially mathematical logic. Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 32. Jan Łukasiewicz gained world fame with his concept of many-valued logic and his " Polish notation." Alfred Tarski's work in truth theory won him world renown.

After World War II, for over four decades, world-class Polish philosophers and historians of philosophy such as Władysław Tatarkiewicz continued their work, often in the face of adversities occasioned by the dominance of a politically enforced official philosophy. The phenomenologist Roman Ingarden did influential work in esthetics and in a Husserl-style metaphysics; his student Karol Wojtyła

Pope John Paul II ( la, Ioannes Paulus II; it, Giovanni Paolo II; pl, Jan Paweł II; born Karol Józef Wojtyła ; 18 May 19202 April 2005) was the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 1978 until his ...

acquired a unique influence on the world stage as Pope John Paul II.

Scholasticism

The formal history of

The formal history of philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

in Poland may be said to have begun in the fifteenth century, following the revival of the University of Kraków by King Władysław II Jagiełło in 1400.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 5.

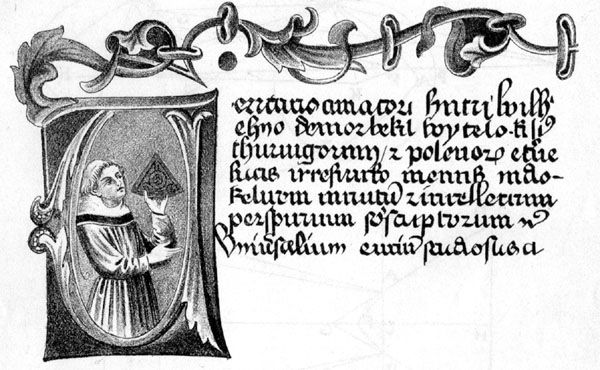

The true beginnings of Polish philosophy, however, reach back to the thirteenth century and Vitello (c. 1230 – c. 1314), a Silesian born to a Polish mother and a Thuringian settler, a contemporary of Thomas Aquinas who had spent part of his life in Italy at centers of the highest intellectual culture. In addition to being a philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

, he was a scientist who specialized in optics. His famous treatise, ''Perspectiva'', while drawing on the Arabic ''Book of Optics

The ''Book of Optics'' ( ar, كتاب المناظر, Kitāb al-Manāẓir; la, De Aspectibus or ''Perspectiva''; it, Deli Aspecti) is a seven-volume treatise on optics and other fields of study composed by the medieval Arab scholar Ibn al- ...

'' by Alhazen

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

, was unique in Latin literature, and in turn helped inspire Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

's best work, Part V of his ''Opus maius'', "On Perspectival Science," as well as his supplementary treatise ''On the Multiplication of Vision''. Vitello's ''Perspectiva'' additionally made important contributions to psychology: it held that vision ''per se'' apprehends only colors and light while all else, particularly the distance and size of objects, is established by means of association and unconscious deduction.

Vitello's concept of being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

was one rare in the Middle Ages, neither Augustinian as among conservatives nor Aristotelian as among progressives, but Neoplatonist. It was an emanationist concept that held radiation

In physics, radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or through a material medium. This includes:

* ''electromagnetic radiation'', such as radio waves, microwaves, infrared, visi ...

to be the prime characteristic of being, and ascribed to radiation the nature of light. This "metaphysic of light" inclined Vitello to optical research, or perhaps ''vice versa'' his optical studies led to his metaphysic.

According to the Polish historian of philosophy, Władysław Tatarkiewicz, no Polish philosopher since Vitello has enjoyed so eminent a European standing as this thinker who belonged, in a sense, to the prehistory of Polish philosophy.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 6.

From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature

From the beginning of the fifteenth century, Polish philosophy, centered at Kraków University, pursued a normal course. It no longer harbored exceptional thinkers such as Vitello, but it did feature representatives of all wings of mature Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

, ''via antiqua'' as well as ''via moderna''.

The first of these to reach Kraków was ''via moderna'', then the more widespread movement in Europe.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 1, p. 311. In physics, logic and ethics, Terminism ( Nominalism) prevailed in Kraków, under the influence of the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

Scholastic, Jean Buridan (died c. 1359), who had been rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the University of Paris and an exponent of views of William of Ockham. Buridan had formulated the theory of "'' impetus''"—the force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a p ...

that causes a body, once set in motion, to persist in motion—and stated that impetus is proportional

Proportionality, proportion or proportional may refer to:

Mathematics

* Proportionality (mathematics), the property of two variables being in a multiplicative relation to a constant

* Ratio, of one quantity to another, especially of a part compare ...

to the speed of, and amount of matter comprising, a body: Buridan thus anticipated Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

and Isaac Newton. His theory of impetus was momentous in that it also explained the motions of celestial bodies

An astronomical object, celestial object, stellar object or heavenly body is a naturally occurring physical entity, association, or structure that exists in the observable universe. In astronomy, the terms ''object'' and ''body'' are often us ...

without resort to the spirits—''"intelligentiae"''—to which the Peripatetics

The Peripatetic school was a school of philosophy in Ancient Greece. Its teachings derived from its founder, Aristotle (384–322 BC), and ''peripatetic'' is an adjective ascribed to his followers.

The school dates from around 335 BC when Aristo ...

(followers of Aristotle) had ascribed those motions. At Kraków, physics was now expounded by (St.) Jan Kanty (1390–1473), who developed this concept of "impetus."

A general trait of the Kraków Scholastics was a provlivity for compromise—for reconciling Nominalism with the older tradition. For example, the Nominalist, Benedict Hesse, while in principle accepting the theory of impetus, did not apply it to the heavenly spheres.

In the second half of the fifteenth century, at Kraków, ''via antiqua'' became dominant. Nominalism retreated, and the old Scholasticism triumphed.

In this period, Thomism had its chief center at Cologne, whence it influenced Kraków. Cologne, formerly the home ground of Albertus Magnus, had preserved Albert's mode of thinking. Thus the Cologne philosophers formed two wings, the Thomist and Albertist, and even Cologne's Thomists showed Neoplatonist traits characteristic of Albert, affirming emanation, a hierarchy

A hierarchy (from Greek: , from , 'president of sacred rites') is an arrangement of items (objects, names, values, categories, etc.) that are represented as being "above", "below", or "at the same level as" one another. Hierarchy is an important ...

of being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

, and a metaphysic of light.

The chief Kraków adherents of the Cologne-style Thomism included Jan of Głogów

Jan, JaN or JAN may refer to:

Acronyms

* Jackson, Mississippi (Amtrak station), US, Amtrak station code JAN

* Jackson-Evers International Airport, Mississippi, US, IATA code

* Jabhat al-Nusra (JaN), a Syrian militant group

* Japanese Article Numb ...

(c. 1445 – 1507) and Jakub of Gostynin

Jakub of Gostynin ( pl, Jakub z Gostynina; c. 1454 – 16 February 1506) was a Polish philosopher and theologian of the late 15th century, and Rector of the University of Krakow in 1503–1504.

Life

Jakub of Gostynin was one of the chief adhere ...

(c. 1454 – 1506). Another, purer teacher of Thomism was Michał Falkener

Michael Falkener, ''Michał z Wrocławia'', ''Michał Wrocławczyk, Michael de Wratislava, Michael Vratislaviensis'' (ca. 1450 or 1460 in Wrocław – 1534) was a Silesian Scholastic philosopher, astronomer, astrologer, mathematician, theolog ...

of Wrocław (c. 1450 – 1534).

Almost at the same time, Scotism appeared in Poland, having been brought from Paris first by Michał Twaróg of Bystrzyków

Michał Twaróg of Bystrzyków ( pl, 'Michał Twaróg z Bystrzykowa'; lat, Michael vulgo Parisiensis de Majori Bystrzyków) (c. 1450–1520) was a Polish philosopher and theologian of the early 16th century.

Life

Michał Twaróg studied at Pari ...

(c. 1450 – 1520). Twaróg had studied at Paris in 1473–77, in the period when, following the anathematization of the Nominalists (1473), the Scotist school was there enjoying its greatest triumphs. A prominent student of Twaróg's, Jan of Stobnica Jan of Stobnica (ca. 1470 - 1530), was a Polish philosopher, scientist and geographer of the early 16th century.

Life

Jan of Stobnica was educated at the Jagiellonian University (Kraków Academy), where he taught as professor between 1498 and 1514. ...

(c. 1470 – 1519), was already a moderate Scotist who took account of the theories of the Ockhamists, Thomists and Humanists.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 7.

When Nominalism was revived in western Europe at the turn of the sixteenth century, particularly thanks to Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (''Faber Stapulensis''), it presently reappeared in Kraków and began taking the upper hand there once more over Thomism and Scotism. It was reintroduced particularly by Lefèvre's pupil, Jan Szylling

Jan Szylling (fl. c. 1500) was a Polish Scholastic philosopher.

Life

Jan Szylling, a native of Kraków, studied with Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples (in Latin, ''Jacobus Faber Stapulensis'') in Paris, France, in the first years of the 16th century. L ...

, a native of Kraków who had studied at Paris in the opening years of the sixteenth century. Another follower of Lefèvre's was Grzegorz of Stawiszyn Grzegorz of Stawiszyn ( pl, Grzegorz ze Stawiszyna; 1481–1540), was a Polish philosopher and theologian of the mid 16th century, Rector of the University of Krakow in the years 1538–1540.

Grzegorz was born in Stawiszyn in 1481. He was an ...

, a Kraków professor who, beginning in 1510, published the Frenchman's works at Kraków.

Thus Poland had made her appearance as a separate philosophical center only at the turn of the fifteenth century, at a time when the creative period of Scholastic

Scholastic may refer to:

* a philosopher or theologian in the tradition of scholasticism

* ''Scholastic'' (Notre Dame publication)

* Scholastic Corporation, an American publishing company of educational materials

* Scholastic Building, in New Y ...

philosophy had already passed. Throughout the fifteenth century, Poland harbored all the currents of Scholasticism. The advent of Humanism in Poland would find a Scholasticism more vigorous than in other countries. Indeed, Scholasticism would survive the 16th and 17th centuries and even part of the 18th at Kraków and Wilno Universities and at numerous Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

, Dominican and Franciscan colleges.

To be sure, in the sixteenth century, with the arrival of the Renaissance, Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

would enter upon a decline; but during the 17th century's Counter-reformation

The Counter-Reformation (), also called the Catholic Reformation () or the Catholic Revival, was the period of Catholic resurgence that was initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation. It began with the Council of Trent (1545–1563) a ...

, and even into the early 18th century, Scholasticism would again become Poland's chief philosophy.

Renaissance

Empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

had flourished at Kraków as early as the fifteenth century, side by side with speculative philosophy. The most perfect product of this blossoming was Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543, pl, Mikołaj Kopernik). He was not only a scientist but a philosopher. According to Tatarkiewicz, he may have been the greatest—in any case, the most renowned—philosopher that Poland ever produced. He drew the inspiration for his cardinal discovery from philosophy; he had become acquainted through Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of ...

with the philosophies of Plato and the Pythagoreans; and through the writings of the philosophers Cicero and Plutarch he had learned about the ancients who had declared themselves in favor of the Earth's movement.

Copernicus may also have been influenced by Kraków philosophy: during his studies there, Terminist physics had been taught, with special emphasis on "'' impetus''." His own thinking was guided by philosophical considerations. He arrived at the heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

thesis (as he was to write in a youthful treatise) "''ratione postea equidem sensu''": it was not observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. The ...

but the discovery of a logical contradiction in Ptolemy's system, that served him as a point of departure that led to the new astronomy. In his dedication to Pope Paul III

Pope Paul III ( la, Paulus III; it, Paolo III; 29 February 1468 – 10 November 1549), born Alessandro Farnese, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 13 October 1534 to his death in November 1549.

He came to ...

, he submitted his work for judgment by "philosophers."Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 9.

In its turn, Copernicus' theory transformed man's view of the structure of the universe, and of the place held in it by the earth and by man, and thus attained a far-reaching philosophical importance.

Copernicus was involved not only in natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

and natural philosophy but also—by his postulation of a quantity theory of money and of " Gresham's Law" (in the year, 1519, of Thomas Gresham's birth)—in the philosophy of man.

In the early sixteenth century, Plato, who had become a model for philosophy in Italy, especially in Medicean

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Mu ...

Florence, was represented in Poland in some ways by Adam of Łowicz Adam of Łowicz (also "Adam of Bocheń" and "''Adamus Polonus''"; born in Bocheń, near Łowicz, Poland; died 7 February 1514, in Kraków, Poland) was a professor of medicine at the University of Krakow, its rector in 1510–1511, a humanist, w ...

, author of ''Conversations about Immortality''.

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian.

Generally speaking, though, Poland remained Aristotelian. Sebastian Petrycy

Sebastian Petrycy of Pilzno (born 1554 in Pilzno – died 1626 in Kraków), in Latin known as Sebastianus Petricius, was a Polish philosopher and physician. He lectured and published notable works in the field of medicine but is principally remem ...

of Pilzno (1554–1626) laid stress, in the theory of knowledge, on experiment and induction; and in psychology, on feeling

Feelings are subjective self-contained phenomenal experiences. According to the ''APA Dictionary of Psychology'', a feeling is "a self-contained phenomenal experience"; and feelings are "subjective, evaluative, and independent of the sensations ...

and will

Will may refer to:

Common meanings

* Will and testament, instructions for the disposition of one's property after death

* Will (philosophy), or willpower

* Will (sociology)

* Will, volition (psychology)

* Will, a modal verb - see Shall and will

...

; while in politics he preached democratic

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

ideas. Petrycy's central feature was his linking of philosophical theory with the requirements of practical national life. In 1601–18, a period when translations into modern languages were still rarities, he accomplished Polish translations of Aristotle's practical works. With Petrycy, vernacular Polish philosophical terminology began to develop not much later than did the French and German.

Yet another Renaissance current, the new Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

, was represented in Poland by Jakub Górski

Jakub Górski (c. 1525 – 1583) was a Polish Renaissance philosopher.

Life

Jakub Górski was an early Polish representative of Stoicism. He wrote a famous ''Dialectic'' (1563) and many works in grammar, rhetoric, theology and sociology. A profe ...

(c. 1525 – 1585), author of a famous ''Dialectic'' (1563) and of many works in grammar, rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

, theology and sociology. He tended toward eclecticism, attempting to reconcile the Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asserting that th ...

with Aristotle.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 10.

A later, purer representative of Stoicism

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy founded by Zeno of Citium in Athens in the early 3rd century Common Era, BCE. It is a philosophy of personal virtue ethics informed by its system of logic and its views on the natural world, asser ...

in Poland was Adam Burski

Adam Burski or Bursius (ca. 1560–1611) was a Polish philosopher of the Renaissance period. Władysław Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'' (History of Philosophy), vol. 2: ''Filozofia nowożytna do roku 1830'' (Modern Philosophy to 1830), 8th e ...

(c. 1560 – 1611), author of a ''Dialectica Ciceronis'' (1604) boldly proclaiming Stoic sensualism and empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological theory that holds that knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empir ...

and—before Francis Bacon—urging the use of inductive method.

Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski

Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski ( la, Andreas Fricius Modrevius) (ca.1503 – autumn 1572) was a Polish Renaissance scholar, humanist and theologian, called "the father of Polish democracy". His book ''De Republica emendanda'' (''O poprawie Rzeczypospol ...

(1503–72), who advocated on behalf of equality for all before the law, the accountability of monarch and government to the nation, and social assistance for the weak and disadvantaged. His chief work was ''De Republica emendanda'' (On Reform of the Republic, 1551–54).

Another notable political thinker was Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki (1530–1607), best known in Poland and abroad for his book ''De optimo senatore'' (The Accomplished Senator, 1568). It propounded the view—which for long got the book banned in England, as subversive of monarchy—that a ruler may legitimately govern only with the sufferance of the people.

After the first decades of the 17th century, the wars, invasions and internal

Another notable political thinker was Wawrzyniec Grzymała Goślicki (1530–1607), best known in Poland and abroad for his book ''De optimo senatore'' (The Accomplished Senator, 1568). It propounded the view—which for long got the book banned in England, as subversive of monarchy—that a ruler may legitimately govern only with the sufferance of the people.

After the first decades of the 17th century, the wars, invasions and internal dissension

Dissension may refer to:

* Expression of dissent

* Strong disagreement

A disagreement is the absence of consensus or consent. It can take the form of dissent or controversy

Controversy is a state of prolonged public dispute or debate, usual ...

s that beset the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, brought a decline in philosophy. If in the ensuing period there was independent philosophical thought, it was among the religious dissenters, particularly the Polish Arians,Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 11. also known variously as Antitrinitarians, Socinians, and Polish Brethren—forerunners of the British and American Socinians, Unitarians

Unitarian or Unitarianism may refer to:

Christian and Christian-derived theologies

A Unitarian is a follower of, or a member of an organisation that follows, any of several theologies referred to as Unitarianism:

* Unitarianism (1565–present) ...

and Deists who were to figure prominently in the intellectual and political currents of the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries.

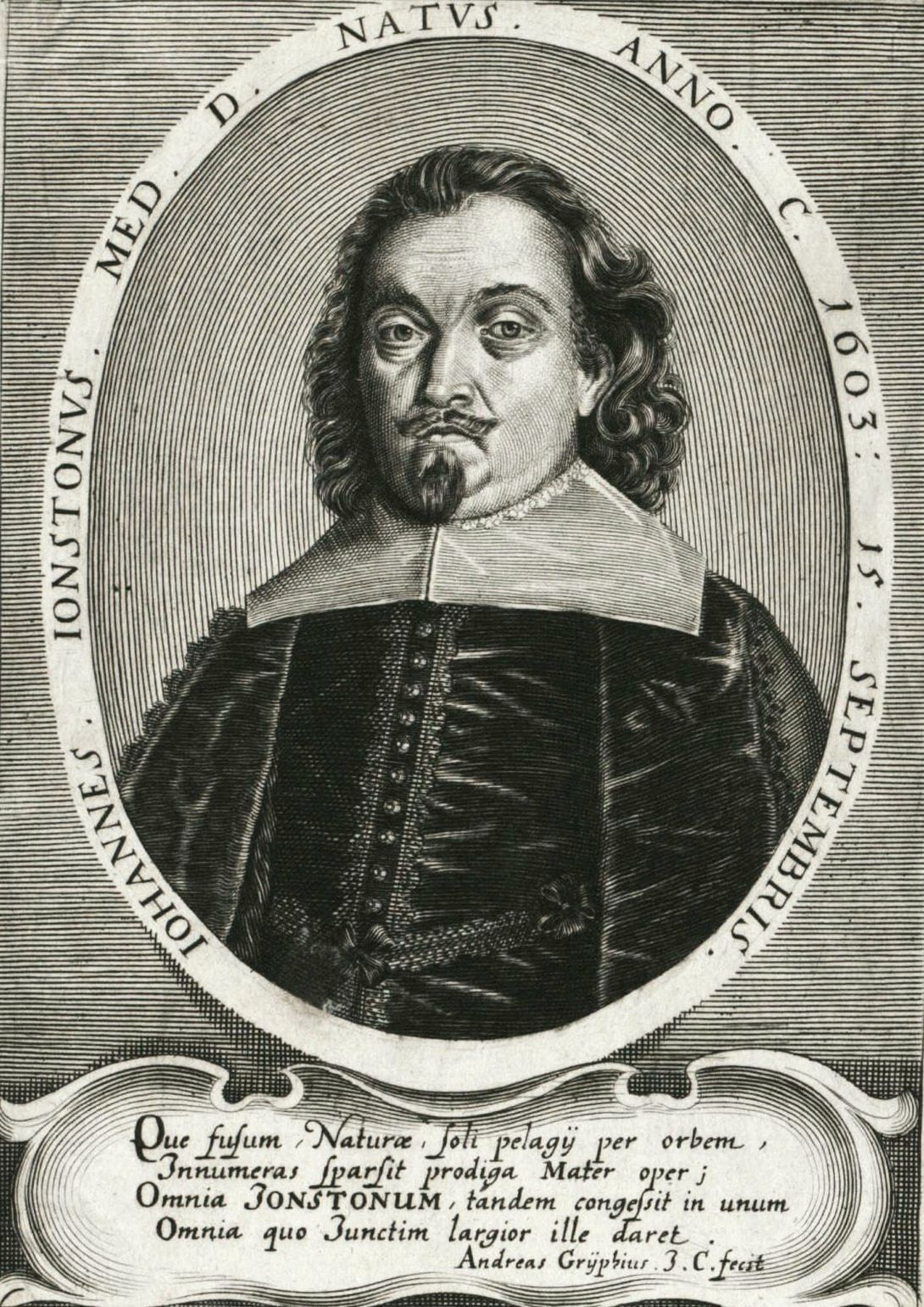

The Polish dissenters created an original ethical theory radically condemning evil and violence. Centers of intellectual life such as that at Leszno hosted notable thinkers such as the Czech pedagogue,

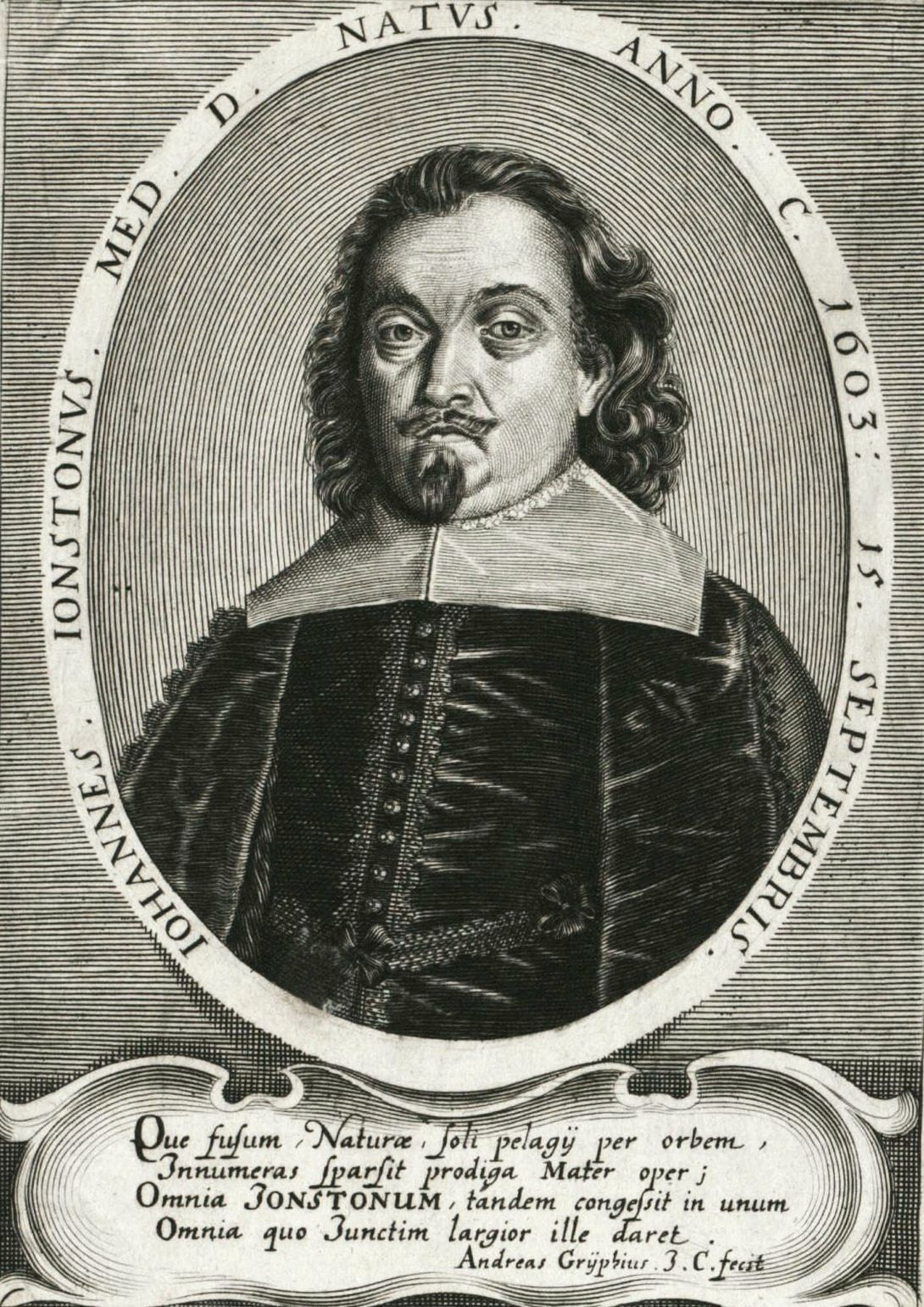

The Polish dissenters created an original ethical theory radically condemning evil and violence. Centers of intellectual life such as that at Leszno hosted notable thinkers such as the Czech pedagogue, Jan Amos Komensky

John Amos Comenius (; cs, Jan Amos Komenský; pl, Jan Amos Komeński; german: Johann Amos Comenius; Latinized: ''Ioannes Amos Comenius''; 28 March 1592 – 15 November 1670) was a Czech philosopher, pedagogue and theologian who is conside ...

(Comenius), and the Pole, Jan Jonston

John Jonston or Johnston ( pl, Jan Jonston; la, Joannes or or ; 15 September 1603– ) was a Polish scholar and physician, descended from Scottish nobility and closely associated with the Polish magnate Leszczyński family.

Life

Jonston wa ...

. Jonston was tutor and physician to the Leszczyński family, a devotee of Bacon and experimental knowledge, and author of ''Naturae constantia'', published in Amsterdam in 1632, whose geometrical method and naturalistic, almost pantheistic concept of the world may have influenced Benedict Spinoza

Baruch (de) Spinoza (born Bento de Espinosa; later as an author and a correspondent ''Benedictus de Spinoza'', anglicized to ''Benedict de Spinoza''; 24 November 1632 – 21 February 1677) was a Dutch philosopher of Portuguese-Jewish origin, b ...

.

The Leszczyński family itself would produce an 18th-century Polish-Lithuanian king, Stanisław Leszczyński (1677–1766; reigned in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth 1704–11 and again 1733–36), "''le philosophe bienfaisant''" ("the beneficent philosopher")—in fact, an independent thinker whose views on culture were in advance of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's, and who was the first to introduce into Polish intellectual life on a large scale the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

influences that were later to become so strong.

In 1689, in an exceptional miscarriage of justice, a Polish ex-Jesuit philosopher, Kazimierz Łyszczyński, author of a manuscript treatise, ''De non existentia Dei'' (On the Non-existence of God), was accused of atheism by a priest who was his debtor, was convicted, and was executed in most brutal fashion.

Enlightenment

Andrzej Stanisław Załuski

Andrzej Stanisław Kostka Załuski (2 December 1695 – 16 December 1758) was a priest (bishop) in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

In his religious career he held the posts of abbot and later Bishop of Płock (from 1723), bishop of Łu ...

.

Scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval school of philosophy that employed a critical organic method of philosophical analysis predicated upon the Aristotelian 10 Categories. Christian scholasticism emerged within the monastic schools that translate ...

, which until then had dominated Polish philosophy, was followed by the Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

. Initially the major influence was Christian Wolff and, indirectly, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth's elected king, August III the Saxon, and the relations between Poland and her neighbor, Saxony, heightened the German influence. Wolff's doctrine was brought to Warsaw in 1740 by the Theatine, Portalupi; from 1743, its chief Polish champion was Wawrzyniec Mitzler de Kolof (1711–78), court physician to August III.

Under the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth's last king, Stanisław August Poniatowski

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1764 to 1795, and the last monarch ...

(reigned 1764–95), the Polish Enlightenment was radicalized and came under French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

influence. The philosophical foundation of the movement ceased to be the Rationalist doctrine of Wolff and became the Sensualism of Condillac. This spirit pervaded Poland's Commission of National Education, which completed the reforms begun by the Piarist priest, Stanisław Konarski. The Commission's members were in touch with the French Encyclopedists and freethinkers, with d'Alembert and Condorcet, Condillac and Rousseau. The Commission abolished school instruction in theology, even in philosophy.

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of

This empiricist and positivist Enlightenment philosophy produced several outstanding Polish thinkers. Although active in the reign of Stanisław August Poniatowski

Stanisław II August (born Stanisław Antoni Poniatowski; 17 January 1732 – 12 February 1798), known also by his regnal Latin name Stanislaus II Augustus, was King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1764 to 1795, and the last monarch ...

, they published their chief works only after the loss of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth's independence in 1795. The most important of these figures were Jan Śniadecki, Stanisław Staszic and Hugo Kołłątaj.

Another adherent of this empirical Enlightenment philosophy was the minister of education under the Duchy of Warsaw and under the Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

established by the Congress of Vienna, Stanisław Kostka Potocki (1755–1821). In some places, as at Krzemieniec and its Lyceum in southeastern Poland, this philosophy was to survive well into the nineteenth century. Although a belated philosophy from a western perspective, it was at the same time the philosophy of the future. This was the period between d'Alembert and Comte; and even as this variety of positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

was temporarily fading in the West, it was carrying on in Poland.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, as Immanuel Kant's fame was spreading over the rest of Europe, in Poland the Enlightenment philosophy was still in full flower. Kantism found here a hostile soil. Even before Kant had been understood, he was condemned by the most respected writers of the time: by Jan Śniadecki, Staszic,

At the turn of the nineteenth century, as Immanuel Kant's fame was spreading over the rest of Europe, in Poland the Enlightenment philosophy was still in full flower. Kantism found here a hostile soil. Even before Kant had been understood, he was condemned by the most respected writers of the time: by Jan Śniadecki, Staszic, Kołłątaj Kołłątaj is a Polish language surname. It is commonly rendered into English without diacritics as Kollataj. The Russian language

Russian (russian: русский язык, russkij jazyk, link=no, ) is an East Slavic languages, East Slavic ...

, Tadeusz Czacki

Tadeusz Czacki (28 August 1765 in Poryck, Volhynia – 8 February 1813 in Dubno) was a Polish historian, pedagogue and numismatist. Czacki played an important part in the Enlightenment in Poland.

Biography

Czacki was born in Poryck in Volhynia, ...

, later by Anioł Dowgird (1776–1835). Jan Śniadecki warned against this "fanatical, dark and apocalyptic mind," and wrote: "To revise Locke

Locke may refer to:

People

*John Locke, English philosopher

*Locke (given name)

*Locke (surname), information about the surname and list of people

Places in the United States

*Locke, California, a town in Sacramento County

*Locke, Indiana

*Locke, ...

and Condillac, to desire ''a priori'' knowledge of things that human nature can grasp only by their consequences, is a lamentable aberration of mind."

Jan Śniadecki's younger brother, however, Jędrzej Śniadecki, was the first respected Polish scholar to declare (1799) for Kant. And in applying Kantian ideas to the natural sciences, he did something new that would not be undertaken until much later by Johannes Müller, Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz and other famous scientists of the nineteenth century.

Another Polish proponent of Kantism was

Another Polish proponent of Kantism was Józef Kalasanty Szaniawski

Józef Kalasanty Szaniawski (1764 in Kalwaria Zebrzydowska – 16 May 1843 in Lwów) was a Polish philosopher and politician.

Life

During the Kościuszko Uprising (1794) Szaniawski was a Polish Jacobins, Polish Jacobin. After the suppression of th ...

(1764–1843), who had been a student of Kant's at Königsberg. But, having accepted the fundamental points of the critical theory of knowledge, he still hesitated between Kant's metaphysical agnosticism and the new metaphysics of Idealism. Thus this one man introduced to Poland both the antimetaphysical Kant and the post-Kantian metaphysics.

In time, Kant's foremost Polish sympathizer would be Feliks Jaroński

Feliks Jaroński (6 June 1777 – 26 December 1827) was a Polish Catholic priest and philosopher.

Life

In 1809–18 Jaroński was a professor at Kraków University. A follower of Kantism, he postulated a renewal of philosophy through the re ...

(1777–1827), who lectured at Kraków in 1809–18. Still, his Kantian sympathies were only partial and this half-heartedness was typical of Polish Kantism generally. In Poland there was no actual Kantian period.

For a generation, between the age of the French Enlightenment and that of the Polish national metaphysic, the Scottish philosophy of common sense became the dominant outlook in Poland. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the Scottish School of Common Sense held sway in most European countries—in Britain till mid-century, and nearly as long in France. But in Poland, from the first, the Scottish philosophy fused with Kantism, in this regard anticipating the West.

The Kantian and Scottish ideas were united in typical fashion by Jędrzej Śniadecki (1768–1838). The younger brother of Jan Śniadecki, Jędrzej was an illustrious scientist, biologist and physician, and the more creative mind of the two. He had been educated at the universities of Kraków, Padua and Edinburgh and was from 1796 a professor at Wilno, where he held a chair of

The Kantian and Scottish ideas were united in typical fashion by Jędrzej Śniadecki (1768–1838). The younger brother of Jan Śniadecki, Jędrzej was an illustrious scientist, biologist and physician, and the more creative mind of the two. He had been educated at the universities of Kraków, Padua and Edinburgh and was from 1796 a professor at Wilno, where he held a chair of chemistry

Chemistry is the science, scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter. It is a natural science that covers the Chemical element, elements that make up matter to the chemical compound, compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions ...

and pharmacy

Pharmacy is the science and practice of discovering, producing, preparing, dispensing, reviewing and monitoring medications, aiming to ensure the safe, effective, and affordable use of medicines. It is a miscellaneous science as it links heal ...

. He was a foe of metaphysics, holding that the fathoming of first causes of being

In metaphysics, ontology is the philosophical study of being, as well as related concepts such as existence, becoming, and reality.

Ontology addresses questions like how entities are grouped into categories and which of these entities exis ...

was "impossible to fulfill and unnecessary." But foe of metaphysics that he was, he was not an Empiricist—and this was his link with Kant. "Experiment and observation can only gather... the materials from which common sense alone can build science."

An analogous position, shunning both positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

and metaphysical speculation, affined to the Scots but linked in some features to Kantian critique, was held in the period before the November 1830 Uprising by virtually all the university professors in Poland: in Wilno, by Dowgird; in Kraków, by Józef Emanuel Jankowski (1790–1847); and in Warsaw, by Adam Ignacy Zabellewicz Adam Ignacy Zabellewicz (1784–1831) was a professor of philosophy at Warsaw University.

Life

Zabellewicz was professor of philosophy at Warsaw University from 1818 to 1823.

Zabellewicz was one of nearly all the university professors of philosoph ...

(1784–1831) and Krystyn Lach Szyrma (1791–1866).

Polish Messianism

Enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

ideas, Poland passed directly to a maximalist philosophical program, to absolute metaphysics, to syntheses, to great systems, to reform of the world through philosophy; and broke with Positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

, the doctrines of the Enlightenment, and the precepts of the Scottish School of Common Sense.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 17.

The Polish metaphysical blossoming occurred between the November 1830 and January 1863 Uprisings, and stemmed from the spiritual aspirations of a politically humiliated people.

The Poles' metaphysic, although drawing on German idealism, differed considerably from it; it was Spiritualist rather than Idealist. It was characterized by a theistic belief in a personal God, in the immortality of souls, and in the superiority of spiritual over corporeal forces.

The Polish metaphysic saw the mission of philosophy not only in the search for truth, but in the reformation of life and in the salvation of mankind. It was permeated with a faith in the metaphysical import of the nation and convinced that man could fulfill his vocation only within the communion of spirits that was the nation, that nations determined the evolution of mankind, and more particularly that the Polish nation had been assigned the role of Messiah to the nations.

These three traits—the founding of a metaphysic on the concept of the soul and on the concept of the nation, and the assignment to the latter of reformative- soteriological tasks—distinguished the Polish metaphysicians. Some, such as Hoene-Wroński, saw the Messiah in philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

itself; others, such as the poet Mickiewicz, saw him in the Polish nation. Hence Hoene-Wroński, and later Mickiewicz, adopted for their doctrines the name, " Messianism". Messianism came to apply generically to Polish metaphysics of the nineteenth century, much as the term " Idealism" does to German metaphysics.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 18.

In the first half of the nineteenth century there appeared in Poland a host of metaphysicians unanimous as to these basic precepts, if strikingly at variance as to details. Their only center was Paris, which hosted Józef Maria Hoene-Wroński (1778–1853). Otherwise they lived in isolation: Bronisław Trentowski

Bronisław Ferdynand Trentowski (21 January 1808 in Opole – 16 June 1869) was a Polish " Messianist" philosopher, pedagogist, journalist and Freemason, and the chief representative of the Polish Messianist "national philosophy.""Trentowski, Broni ...

(1808–69) in Germany; Józef Gołuchowski

Józef Wojciech Gołuchowski (1797 – 22 November 1858) was a Polish philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, me ...

(1797–1858) in Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

; August Cieszkowski (1814–94) and Karol Libelt

Karol Libelt (8 April 1807, neighborhood of Chwaliszewo in Poznań, Duchy of Warsaw - 9 June 1875, Brdowo) was a Polish philosopher, writer, political and social activist, social worker and liberal, nationalist politician, and president of the Po ...

(1807–75) in Wielkopolska (western Poland); Józef Kremer (1806–75) in Kraków. Most of them became active only after the November 1830 Uprising.

An important role in the Messianist movement was also played by the Polish Romantic poets, Adam Mickiewicz (1798–1855), Juliusz Słowacki (1809–49) and Zygmunt Krasiński (1812–59), as well as by religious activists such as Andrzej Towiański

Andrzej Tomasz Towiański (; January 1, 1799 – May 13, 1878) was a Polish philosopher and messianic religious leader.

Life

Towiański was born in Antoszwińce, a village near Vilnius, which after Partitions of Poland belonged to the Russian ...

(1799–1878).

Between the philosopher

A philosopher is a person who practices or investigates philosophy. The term ''philosopher'' comes from the grc, φιλόσοφος, , translit=philosophos, meaning 'lover of wisdom'. The coining of the term has been attributed to the Greek th ...

s and the poets, the method of reasoning, and often the results, differed. The poets desired to create a specifically ''Polish'' philosophy, the philosophers—an absolute ''universal'' philosophy. The Messianist philosophers knew contemporary European philosophy and drew from it; the poets created more of a home-grown metaphysic.

The most important difference among the Messianists was that some were rationalists, others mystics. Wroński's philosophy was no less rationalist than Hegel

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (; ; 27 August 1770 – 14 November 1831) was a German philosopher. He is one of the most important figures in German idealism and one of the founding figures of modern Western philosophy. His influence extends a ...

's, while the poets voiced a mystical philosophy.

The Messianists were not the only Polish philosophers active in the period between the 1830 and 1863 uprisings. Much more widely known in Poland were Catholic thinkers such as Father Piotr Semenenko (1814–86), Florian Bochwic

Florian may refer to:

People

* Florian (name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

* Florian, Roman emperor in 276 AD

* Saint Florian (250 – c. 304 AD), patron saint of Poland and Upper Austria, al ...

(1779–1856) and Eleonora Ziemięcka

Eleonora Ziemięcka (''ne'' Gagatkiewicz) (born 1819 in Jasieniec, Grójec County, Jasieniec in Mazovia, died September 23, 1869 in Warsaw) - was a Polish philosopher and publicist. She is often considered to be Poland's first female philosopher. ...

(1819–69), Poland's first woman philosopher. The Catholic philosophy of the period was more widespread and fervent than profound or creative. Also active were pure Hegelians such as Tytus Szczeniowski Tytus is a human name that can serve as a given name or surname.

People with the first name of Tytus

*Tytus Czyżewski (1880-1945), Polish painter, art theoretician, Futurist poet, playwright, member of the Polish Formists, and Colorist

*Tytus Mak ...

(1808–80) and leftist Hegelians such as Edward Dembowski

Edward Dembowski (25 April or 31 May 1822 – 27 February 1846) was a Polish philosopher, literary critic, journalist, and leftist independence activist."Dembowski, Edward," ''Encyklopedia Polski'' (Encyclopedia of Poland), p. 128.

Life

Edward De ...

(1822–46).

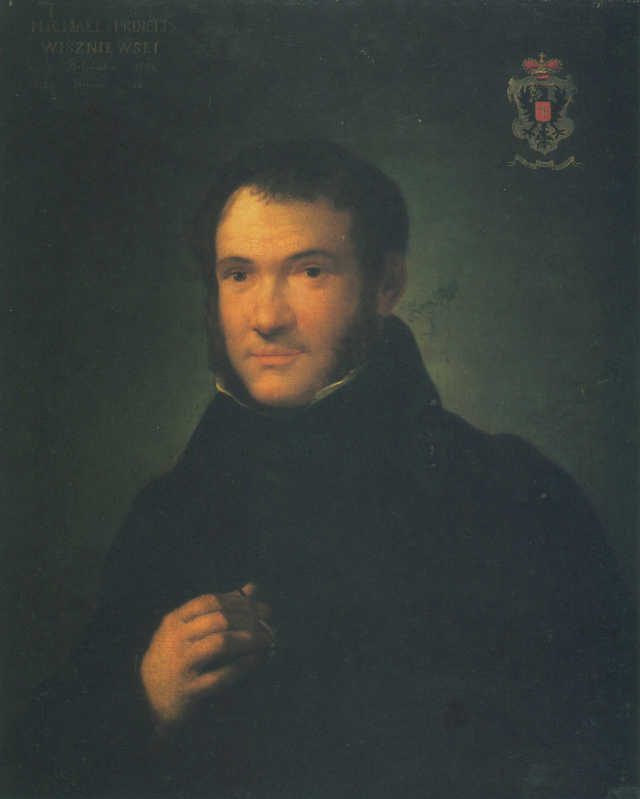

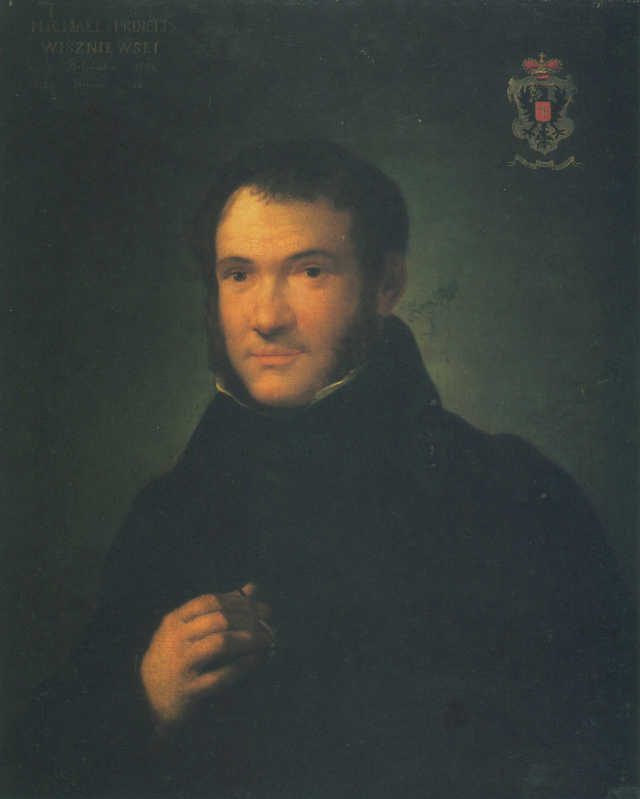

An outstanding representative of the philosophy of Common Sense, Michał Wiszniewski (1794–1865), had studied at that Enlightenment bastion, Krzemieniec; in 1820, in France, he had attended the lectures of Victor Cousin; and in 1821, in Britain, he had met the head of the Scottish School of Common Sense at the time, Dugald Stewart.

Active as well were precursors

Precursor or Precursors may refer to:

* Precursor (religion), a forerunner, predecessor

** The Precursor, John the Baptist

Science and technology

* Precursor (bird), a hypothesized genus of fossil birds that was composed of fossilized parts of un ...

of Positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

such as Józef Supiński

Józef Supiński (village of Romanów, near Lwów, 21 February 1804 – 16 February 1893, Lwów) was a Polish philosopher, jurist, economist and sociologist.

Life

A student at Warsaw University, Supiński in 1831 left for Paris, because he had ...

(1804–93) and Dominik Szulc

Dominik Szulc (June 10, 1787 – December 27, 1860) was a Polish philosopher, historian, and a significant precursor to Polish positivism.

In 1814 he began studies at the University of Vilnius. In 1818 became a teacher of Polish language in hig ...

(1797–1860)—links between the earlier Enlightenment age of the brothers Śniadecki and the coming age of Positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

.

Positivism

The Positivist philosophy that took form in Poland after the

The Positivist philosophy that took form in Poland after the January 1863 Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

was hardly identical with the philosophy of Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...

. It was in fact a return to the line of Jan Śniadecki and Hugo Kołłątaj—a line that had remained unbroken even during the Messianist period—now enriched with the ideas of Comte.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 3, p. 176. However, it belonged only partly to philosophy

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Some ...

. It combined Comte's ideas with those of John Stuart Mill

John Stuart Mill (20 May 1806 – 7 May 1873) was an English philosopher, political economist, Member of Parliament (MP) and civil servant. One of the most influential thinkers in the history of classical liberalism, he contributed widely to ...

and Herbert Spencer, for it was interested in what was common to them all: a sober, empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

attitude to life.

The Polish Positivism was a reaction against philosophical speculation, but also against romanticism in poetry and idealism in politics. It was less a scholarly movement than literary, political and social. Few original books were published, but many were translated from the philosophical literature of the West—not Comte himself, but easier writers: Hippolyte Taine, Mill, Spencer, Alexander Bain, Thomas Henry Huxley, the Germans Wilhelm Wundt

Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt (; ; 16 August 1832 – 31 August 1920) was a German physiologist, philosopher, and professor, known today as one of the fathers of modern psychology. Wundt, who distinguished psychology as a science from philosophy and ...

and Friedrich Albert Lange, the Danish philosopher Höffding.

The disastrous outcome of the January 1863 Uprising

The January Uprising ( pl, powstanie styczniowe; lt, 1863 metų sukilimas; ua, Січневе повстання; russian: Польское восстание; ) was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at ...

had produced a distrust of romanticism, an aversion to ideals and illusions, and turned the search for redemption toward sober thought and work directed at realistic goals. The watchword became "organic work"—a term for the campaign for economic improvement, which was regarded as a prime requisite for progress. Poles prepared for such work by studying the natural sciences and economics: they absorbed Charles Darwin's biological theories, Mill's economic theories, Henry Thomas Buckle's deterministic

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

theory of civilization. At length they became aware of the connection between their own convictions and aims and the Positivist philosophy of Auguste Comte

Isidore Marie Auguste François Xavier Comte (; 19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher and writer who formulated the doctrine of positivism. He is often regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense ...

, and borrowed its name and watchwords.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 3, p. 177.

This movement, which had begun still earlier in Austrian-ruled

This movement, which had begun still earlier in Austrian-ruled Galicia

Galicia may refer to:

Geographic regions

* Galicia (Spain), a region and autonomous community of northwestern Spain

** Gallaecia, a Roman province

** The post-Roman Kingdom of the Suebi, also called the Kingdom of Gallaecia

** The medieval King ...

, became concentrated with time in the Russian-ruled Congress Poland

Congress Poland, Congress Kingdom of Poland, or Russian Poland, formally known as the Kingdom of Poland, was a polity created in 1815 by the Congress of Vienna as a semi-autonomous Polish state, a successor to Napoleon's Duchy of Warsaw. It w ...

centered about Warsaw and is therefore commonly known as the "Warsaw Positivism." Its chief venue was the Warsaw ''Przegląd Tygodniowy'' (Weekly Review); Warsaw University (the "Main School") had been closed by the Russians in 1869.

The pioneers of the Warsaw Positivism were natural scientists and physicians rather than philosophers, and still more so journalists and men of letters

''Men of Letters: The Post Office Heroes who Fought the Great War'' is a book by Duncan Barrett, co-author of ''The Sugar Girls'' and ''GI Brides'' and editor of ''The Reluctant Tommy''. It was published by AA Publishing on 1 August 2014 and offic ...

: Aleksander Świętochowski (1849–1938), Piotr Chmielowski (1848–1904), Adolf Dygasiński

Adolf Dygasiński (March 7, 1839, Niegosławice – June 3, 1902, Grodzisk Mazowiecki) was a Polish novelist, publicist and educator. In Polish literature, he was one of the leading representatives of Naturalism.

Life

During his literary career ...

(1839–1902), Bolesław Prus (1847–1912). Prus developed an original Utilitarian-inspired ethical system in his book, '' The Most General Life Ideals''; his 1873 public lecture '' On Discoveries and Inventions'', subsequently printed as a pamphlet, is a remarkably prescient contribution to what would, in the following century, become the field of logology ("the science of science").

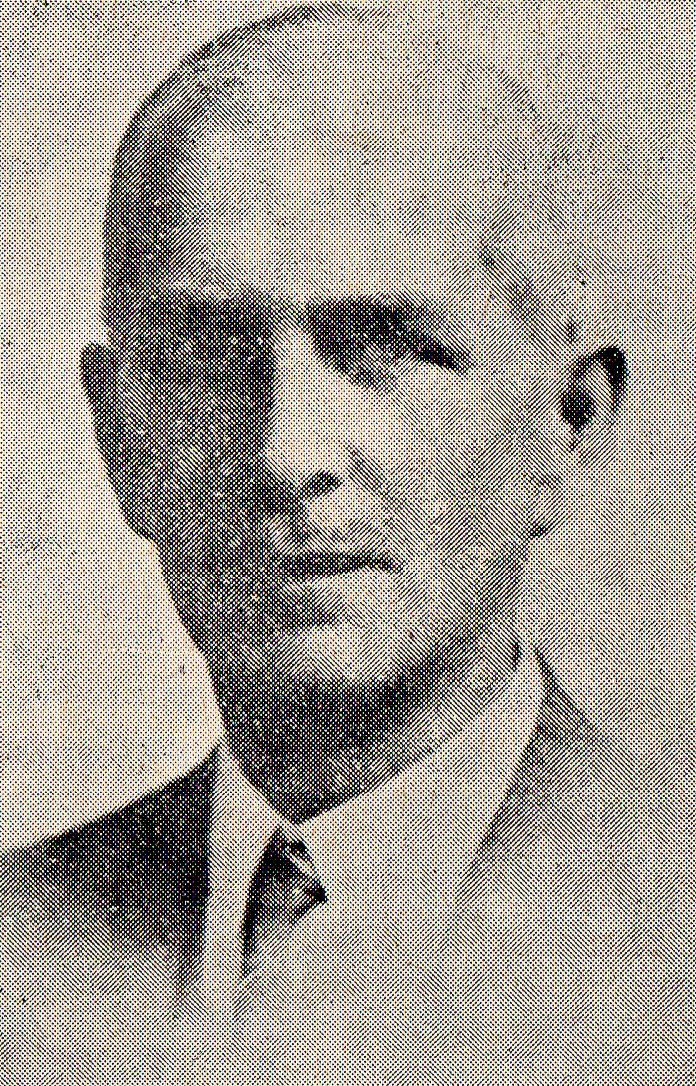

The most brilliant philosophical mind in this period was

The most brilliant philosophical mind in this period was Adam Mahrburg

Adam Mahrburg (6 August 1855 – 13 November 1913) was a Polish philosopher—the outstanding philosophical mind of Poland's Positivist period.Jan Zygmunt Jakubowski, ed., ''Literatura polska od średniowiecza do pozytywizmu'' (Polish Literature f ...

(1855–1913). He was a Positivist in his understanding of philosophy as a discipline and in his uncompromising ferreting out of speculation, and a Kantian in his interpretation of mind and in his centering of philosophy upon the theory of knowledge.

In Kraków, Father Stefan Pawlicki

Stefan Zachariasz Pawlicki (2 September 1839, Danzig (Gdańsk) – 28 April 1916, Kraków) was a Polish Catholic priest, philosopher, historian of philosophy, professor and rector of Kraków's Jagiellonian University.Information from the Polish Wi ...

(1839–1916), professor of philosophy at the University of Kraków, was a man of broad culture and philosophical bent, but lacked talent for writing or teaching. Under his thirty-plus-year tenure, Kraków philosophy became mainly a historical discipline, alien to what was happening in the West and in Warsaw.

20th century

Even before Poland regained independence at the end of World War I, her intellectual life continued to develop. This was the case particularly in Russian-ruled Warsaw, where in lieu of underground lectures and secret scholarly organizations a '' Wolna Wszechnica Polska'' (Free Polish University) was created in 1905 and the tireless Władysław Weryho (1868–1916) had in 1898 founded Poland's first philosophical journal, ''Przegląd Filozoficzny'' (The Philosophical Review), and in 1904 a Philosophical Society.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 3, p. 356.

In 1907 Weryho founded a Psychological Society, and subsequently Psychological and Philosophical Institutes. About 1910 the small number of professionally trained philosophers increased sharply, as individuals returned who had been inspired by Mahrburg's underground lectures to study philosophy in Austrian-ruled

Even before Poland regained independence at the end of World War I, her intellectual life continued to develop. This was the case particularly in Russian-ruled Warsaw, where in lieu of underground lectures and secret scholarly organizations a '' Wolna Wszechnica Polska'' (Free Polish University) was created in 1905 and the tireless Władysław Weryho (1868–1916) had in 1898 founded Poland's first philosophical journal, ''Przegląd Filozoficzny'' (The Philosophical Review), and in 1904 a Philosophical Society.Tatarkiewicz, ''Historia filozofii'', vol. 3, p. 356.

In 1907 Weryho founded a Psychological Society, and subsequently Psychological and Philosophical Institutes. About 1910 the small number of professionally trained philosophers increased sharply, as individuals returned who had been inspired by Mahrburg's underground lectures to study philosophy in Austrian-ruled Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

and Kraków or abroad.

Kraków as well, especially after 1910, saw a quickening of the philosophical movement, particularly at the Polish Academy of Learning, where at the prompting of

Kraków as well, especially after 1910, saw a quickening of the philosophical movement, particularly at the Polish Academy of Learning, where at the prompting of Władysław Heinrich Władysław Heinrich (Warsaw, 1 January 1869 – 30 June 1957, Kraków, Poland) was a Polish historian of philosophy, psychologist, professor at Kraków University and member of the Polish Academy of Learning.

Life

Władysław Heinrich studied math ...

there came into being in 1911 a Committee for the History of Polish Philosophy and there was an immense growth in the number of philosophical papers and publications, no longer only of a historical

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbrella term comprising past events as well ...

character.Tatarkiewicz, ''Zarys...'', p. 27.

At Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

, Kazimierz Twardowski (1866–1938) from 1895 stimulated a lively philosophical movement, in 1904 founded the Polish Philosophical Society

The Polish Philosophical Society is a scientific society based in Poland, founded in 1904 in Lwów by Kazimierz Twardowski.

The statutory goal is to practice and promote philosophy, especially onthology, theory of knowledge, logic, methodology, e ...

, and in 1911 began publication of '' Ruch Filozoficzny'' (The Philosophical Movement).

There was growing interest in western philosophical currents, and much discussion of Pragmatism and Bergsonism

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson

, psychoanalysis, Henri Poincaré

Jules Henri Poincaré ( S: stress final syllable ; 29 April 1854 – 17 July 1912) was a French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as "The ...

's Conventionalism, Edmund Husserl's Phenomenology

Phenomenology may refer to:

Art

* Phenomenology (architecture), based on the experience of building materials and their sensory properties

Philosophy

* Phenomenology (philosophy), a branch of philosophy which studies subjective experiences and a ...

, the Marburg School, and the social-science methodologies of Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held G. W. F. Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, w ...

and Heinrich Rickert. At the same time, original ideas developed on Polish soil.

Those who distinguished themselves in Polish philosophy in these pre- World War I years of the twentieth century, formed two groups.

One group developed apart from

Those who distinguished themselves in Polish philosophy in these pre- World War I years of the twentieth century, formed two groups.

One group developed apart from institutions of higher learning

Tertiary education, also referred to as third-level, third-stage or post-secondary education, is the educational level following the completion of secondary education. The World Bank, for example, defines tertiary education as including univers ...

and learned societies, and appealed less to trained philosophers than to broader circles, which it (if but briefly) captured. It constituted a reaction against the preceding period of Positivism

Positivism is an empiricist philosophical theory that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning ''a posteriori'' facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience.John J. Macionis, Linda M. G ...

, and included Stanisław Brzozowski (1878–1911), Wincenty Lutosławski (1863–1954) and, to a degree, Edward Abramowski

Edward Józef Abramowski (17 August 1868 – 21 June 1918) was a Polish philosopher, libertarian socialist, anarchist, psychologist, ethician, and supporter of cooperatives. Abramowski is also one of the best known activists of classical anarch ...

(1868–1918).

The second group of philosophers who started off Polish philosophy in the twentieth century had an academic character. They included

The second group of philosophers who started off Polish philosophy in the twentieth century had an academic character. They included Władysław Heinrich Władysław Heinrich (Warsaw, 1 January 1869 – 30 June 1957, Kraków, Poland) was a Polish historian of philosophy, psychologist, professor at Kraków University and member of the Polish Academy of Learning.

Life

Władysław Heinrich studied math ...

(1869–1957) in Kraków, Kazimierz Twardowski (1866–1938) in Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

, and Leon Petrażycki

Leon Petrażycki (Polish: Leon Petrażycki; Russian: ''Лев Иосифович Петражицкий'' ev Iosifovich Petrazhitsky born 13 April 1867, in Kołłątajewo, Mogilev Governorate, now in Belarus – 15 May 1931, in Warsaw) was a Poli ...